We all have varying comfort levels with how far from everyday comforts we can go before it feels we achieve isolation. Take for example camping, when we turn to nature to help reset and recover from the hectic pace of a normal routine. Some are quite happy to go to the local park for a couple of nights car camping, others need a few nights away from roads on a backcountry backpacking trip – some even do months on the trail to complete hikes such as the Pacific Crest Trail or the Appalachian trail.

In some ways, just getting on a ship achieves this break from the normal – you enter a self-contained community and while communications with shore have drastically improved through the years, they are still often at least speed limited. Everything you need is on board, and the most important ‘news’ often comes from the ship’s internal server reporting when you’ve reached the next station or when samples are about to reach the deck. Just as there are no stores out here, we also can’t just pull into a port if something breaks – if it breaks, we’ve got to be able to fix it ourselves- technicians, engineers, electricians, and even a medical doctor are on board. On non- remote voyages you often have a medical officer (first aid to full EMT qualifications in many cases), but for any voyage deemed remote a doctor is necessary.

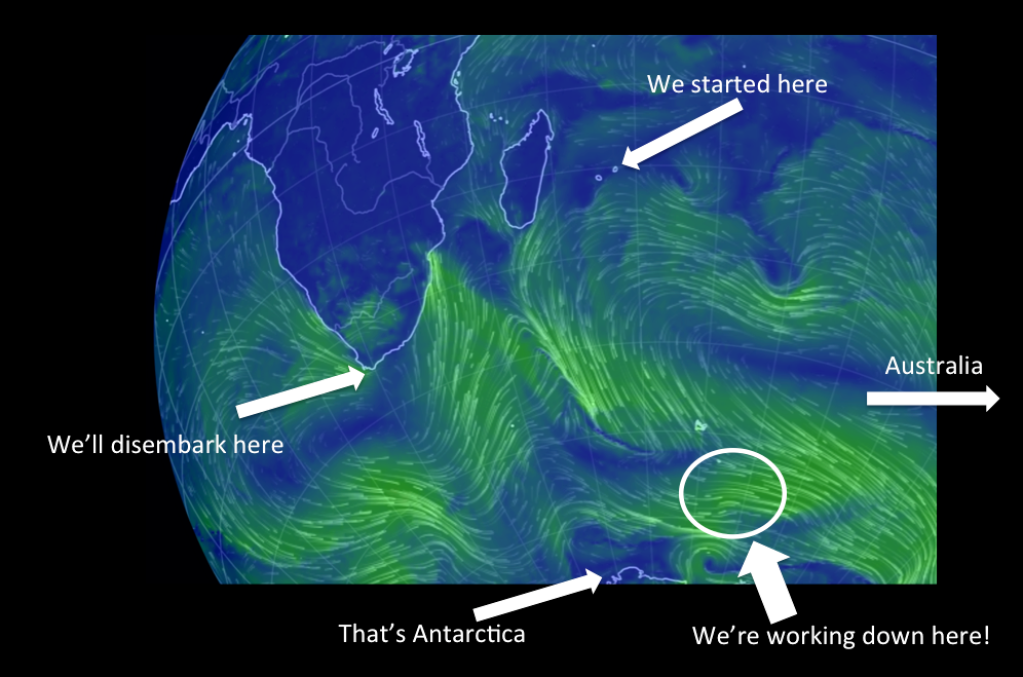

Why is this trip classified as ‘remote’ even in a field where to many, all voyages feel, at least to some degree, remote? Well the map above should help, Kerguelen really is not near any populated area. As I mentioned in a previous post, we’re over 7 days transit away from Mauritius. That means, for more than a week the ship steamed at 12 knots (about 22 km/hour – a very reasonable speed for a vessel this size) 24 hours a day to get here. At the end of our trip, our transit will be nearly two weeks at the same pace (if the weather cooperates) to get to Cape Town. The dominant winds and surface ocean currents will also be working against us on our way to Cape Town, so even if we’re making 12 knots through the water, our ground speed (that is how fast we’re actually travelling compared to land/seafloor) will be lower (e.g. if we’re going 12 knots into a 4 knot current, our ground speed will only be 8 knots 12 – 4 = 8). In summary, we’re a long ways from anywhere.

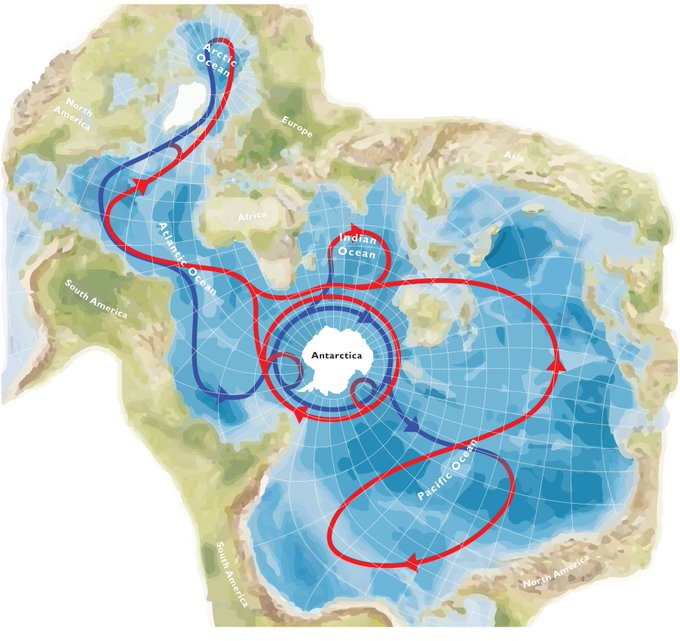

So why is Kerguelen special? What brought our group of 23 scientists and 31 crew members on RV Sonne for nearly 2 months all the way down to 58 degrees South? Kerguelen Plateau is an elevated area in the Southern Ocean, the geology of the region makes the area shallower than its surroundings and this interferes with circulation patterns in the Southern Ocean. By causing these interruptions to the flow of currents such as the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, the Kerguelen Plateau becomes a prime location to look for sediment records of past climate and ocean circulation changes – and its proximity to Antarctica means the region represents high latitude changes through time. Both the structure of the sediment deposits (seismic) and the composition of the sediment (coring) can help us learn about the changes in regional climate and circulation through time and we’ll be doing both on this trip. Most voyages have at least two or three different groups collecting different datasets on board. This provides (often complimentary) data, and a little more time for sleep when the ship is focused on another group’s objectives. And this trip is no different- we’re doing seismics, Parasound®, bathymetry, mammal observations, and geology.

Any time a ship goes into a region with little ship traffic, there is the opportunity to help expand coverage of global monitoring efforts. One such program, ARGO, consists of between 3000 and 4000 active floats taking measurements of temperature, salinity, and velocity in the top 2 km of the ocean. The floats are free floating, and drift with the currents going through a measurement cycle about every 10 days that ends with a surface interval to allow the float to send home its data. Each float has an estimated lifetime of 4 to 5 years, with about 800 floats deployed globally each year since 2000. The data from these floats is providing a quantitative description of the upper ocean variability including information about heat and freshwater storage and transport over scales of months to decades. All data is publically available from Global Data Assembly Centers in near real-time.

Want to follow our floats? Check out data for Argo float numbers 1061, 1079, 1054, 1080, 8847, 8830, and 8846.

Want more from the voyage? Check out the official voyage weekly reports, click the week number listed after SO272 (2020 Indic) and you can view all 7 weekly reports.